United Kingdom’s Critical Infrastructure Under Strain

November 26, 2025

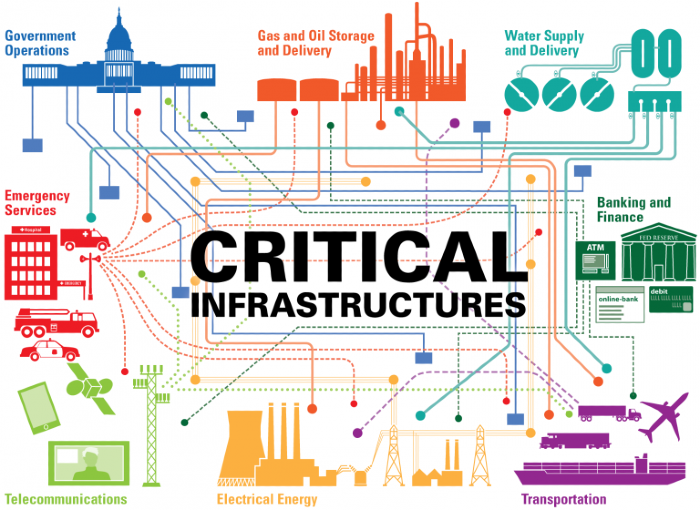

The United Kingdom is entering a decisive phase in the defense of its critical infrastructure, confronted with a convergence of structural fragilities and increasingly aggressive cyber activity. Years of accumulated technical debt, hundreds of legacy systems still operating at the core of public services, and a regulatory framework that no longer reflects the tempo of modern attacks have created a strategic exposure window that adversaries continue to exploit. Recent assessments show a landscape marked by ageing technologies, unpatched vulnerabilities, and escalating operational costs, while state-sponsored intrusion sets actively map and probe essential sectors—energy, water, transport, healthcare—seeking long-term access. Against this backdrop, the government has begun to reposition itself, recognising cyber threats as the leading national security risk and responding with a new legislative push designed to force modernization, enhance resilience, and impose accountability across operators of essential services. This survey examines how legacy dependencies, adversarial intent and regulatory transformation now intersect to shape the future security of the UK’s vital systems, and why the timeline for remediation is rapidly closing.

Legacy load and inventory

The UK is carrying an accumulated load of structural cyber risk that comes directly from its dependence on legacy systems. Government assessments list 228 legacy systems inside public administration alone, and more than 25% of them are already categorised as high-risk for operational or security failure. This situation mirrors a global pattern—by 2020 almost 50% of business network assets were already ageing or obsolete—yet the UK stands out because the concentration of outdated systems inside critical sectors is higher than in comparable economies. A five-country benchmark places the UK with a vulnerability score of 92, higher than the US, Germany, France and Japan, largely because of persistent technical debt across utilities, healthcare, transport and core government functions.

Exploitation vector: unpatched vulnerabilities

Attackers exploit the drag created by these outdated platforms. Across Europe, 60% of cyber breaches in 2022–2023 came from unpatched vulnerabilities, the type that proliferate when systems reach end-of-support. Healthcare is a visible example. France disclosed that 60% of hospitals were still using Windows 7 in 2022, and UK healthcare services follow similar patterns, creating a consistent entry point for ransomware crews, access brokers and state-linked intrusion sets. The adversarial ecosystem has adapted accordingly: hybrid operations probing OT networks, foreign intelligence services mapping water, energy and transportation systems, and criminal affiliates leveraging initial-access markets. The February 2024 US advisories about Volt Typhoon targeting water, energy and transport illustrate the scale of the operational playbook, and UK agencies assess similar patterns inside their own critical infrastructure telemetry.

Economic drag of technical debt

The economic burden produced by obsolete systems is becoming unsustainable. The US example shows the dynamic clearly: $100 billion spent in 2023 on IT and cybersecurity, $80 billion of which was consumed simply by keeping legacy systems alive. That same imbalance exists inside UK public services and private operators, draining resources that should be directed toward modernization. When failures happen, the costs escalate far beyond technology budgets. An average outage costs $9,000 per minute, and more than half of downtime incidents originate from cyber compromise. The Synnovis attack in 2024 demonstrated how technical debt converts directly into societal harm: $39 million in direct costs, disruptions affecting more than 11,000 patients, supply-chain delays and service cancellations across hospitals.

Threat intent and operational reconnaissance

The government has now recognised the structural problem. Cyberattacks have been publicly designated as the leading national security threat, surpassing terrorism and espionage. Internal reviews concluded that the 2018 NIS framework is outdated and no longer aligned with the operational tempo of current attacks. The analysis highlighted persistent probing of energy grids, transport networks, healthcare systems and communications, combined with structural weaknesses: fragmented oversight, inconsistent procurement standards, slow patch cycles and a regulatory environment unable to impose fast corrective action.

Regulatory and legislative pivot

In reaction, the UK is pivoting to a new legislative and regulatory posture that forces institutions into a modern security era. New laws will impose stronger cybersecurity standards across hospitals, energy and water operators, transport networks, digital infrastructure providers and essential services. The measures include mandatory risk assessments, continuous monitoring, strict OT-system protection, improved data safeguards, and auditing mechanisms backed by penalties for non-compliance. Directors and senior leaders are now expected to assume explicit oversight responsibility for cyber risk, anchoring accountability at governance level rather than leaving it to overstretched technical teams.

Operational support and cultural shift

The National Cyber Security Centre is expanding support to operators—training, guidance, incident-response coordination—but the reforms are fundamentally about shifting culture, not adding paperwork. Organisations are expected to prioritise controls that produce measurable risk reduction, not to chase exhaustive compliance checklists that do little to protect against real-world attackers. Eliminating technical debt, patching unsupported systems, rolling out phishing-resistant authentication, segmenting OT networks and building resilience architectures are now treated as immediate national priorities, not long-term aspirations.

Failure mode and strategic consequence

If this transition fails, the UK faces an intensifying cycle of cascading failures: supply-chain intrusions, synchronized ransomware operations, cross-sector outages spreading from water to transport to healthcare, and economic losses far exceeding current projections. If it succeeds, the country can convert a decade of accumulated vulnerability into a long-overdue resilience architecture. But the window is narrow. Attack velocity is rising, legacy exposure remains high, and adversaries—state and criminal—are accelerating. Modernisation has to outpace them, otherwise the next Synnovis-level incident will be larger, faster and more strategically disruptive.