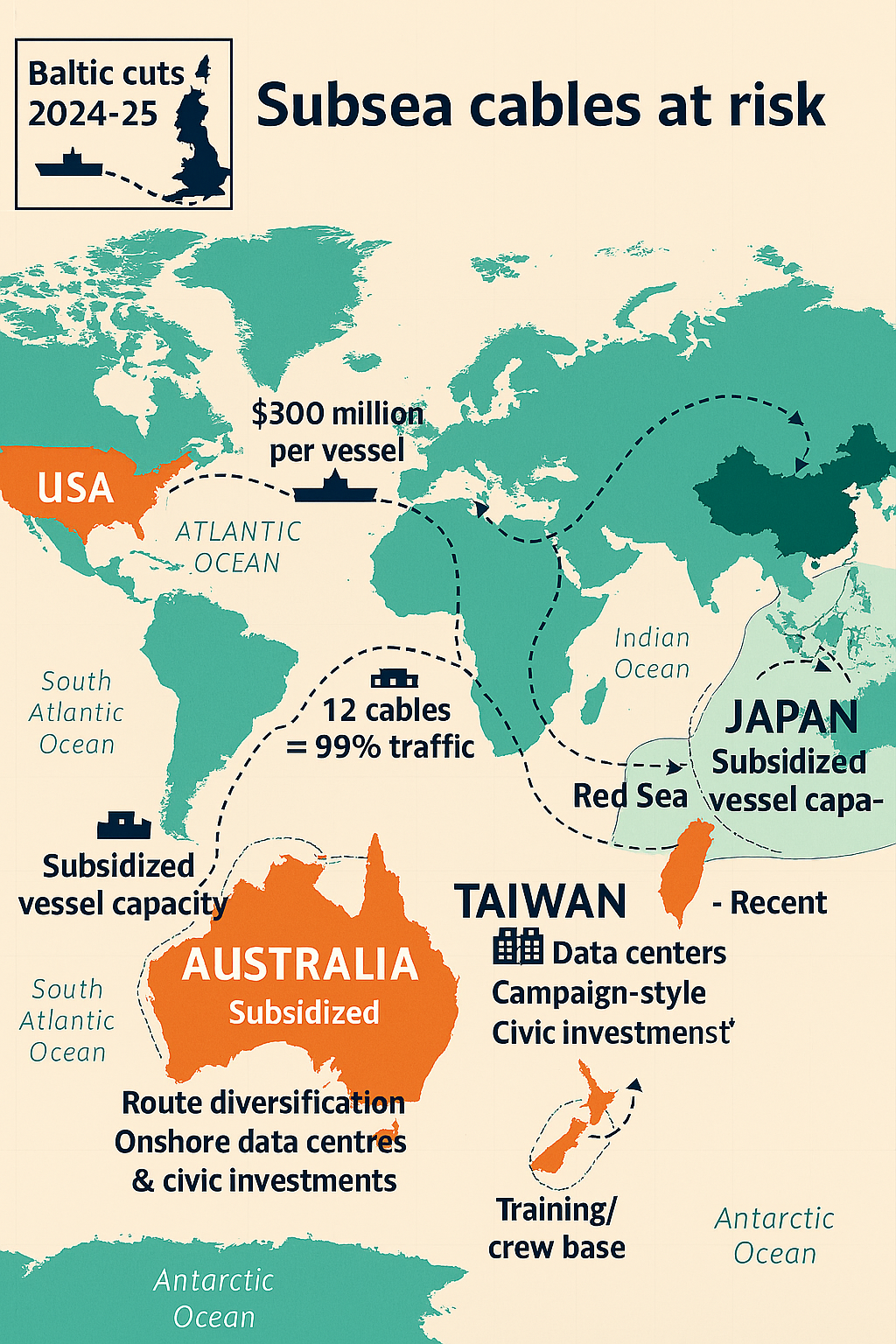

Subsea Cables at Risk Strategic Survey: Japan’s Fleet Push and Australia’s Resilience Imperative

September 17, 2025

Undersea cables carry the bulk of global communications and financial traffic, and recent cuttings and suspected sabotages have transformed them from commercial infrastructure into front‑line national‑security assets. Japan is moving to underwrite ocean‑going cable‑laying vessels for NEC to guarantee sovereign repair and lay capability. Australia, hugely dependent on a dozen international cables for 99 percent of its external connectivity, frames the problem as both a technical vulnerability and a civic challenge: physical redundancy must be paired with social cohesion, trained crews and national will. This survey merges both national responses into a single view of threats, operational trade‑offs and a pragmatic policy agenda.

Strategic stakes and shared threat picture

Undersea cables are strategic arteries: they carry most internet traffic, cloud connectivity, and daily financial flows measured in trillions of dollars. Minutes of physical interference can produce hours or months of disruption, and damage in international waters often sits below the threshold of a clear act of war, complicating attribution and legal response. Adversaries or accidents can sever links, tap fibres covertly, or exploit opaque vessel ownership to deny or delay repairs. Recent precedents include multiple European outages from late 2024 into 2025 and suspected freighter strikes on U.S.–Taiwan links; Taiwan now patrols landing cables. These events crystallise the core vulnerability both Tokyo and Canberra are addressing.

Japan’s industrial response and rationale

Tokyo is prepared to subsidise up to half the acquisition cost of ocean‑going cable‑laying vessels for NEC; individual ships are priced at about $300 million, implying sizeable public exposure if multiple vessels are bought. NEC is Asia’s largest installer with over 400,000 km laid but currently lacks owned ocean‑crossing ships and relies on charters — notably a Norwegian‑chartered vessel with an upcoming expiry — and smaller domestic vessels from NTT and KDDI that operate only in regional waters. The government’s case is straightforward: sovereign access to lay‑and‑repair ships shortens response time, reduces dependence on foreign legal regimes and operators that may be constrained in crises, and strengthens deterrence by removing a predictable commercial chokepoint. The countervailing commercial risk is real: vessels are capital‑intensive fixed assets that can become a heavy burden if market demand softens.

Australia’s resilience framing and civic dimension

Australia depends on roughly 12 major cables for 99 percent of its international internet traffic; the nation’s exposure is structural and immediate. The policy discourse links technical remedies (route diversification, onshore data centres, rapid‑repair capacity) with social renewal: civic education, national‑service‑style programs and community‑oriented infrastructure projects that bind new migrants and long‑term residents to shared security responsibilities. The argument is explicit: without social cohesion the political will and human resources to build and defend resilient networks evaporate. Australia’s defence manpower shortfall (circa 4,300 personnel below authorised strength) underscores the human limits to surge responses and reinforces the need for a broader civic recruitment and training pipeline for marine‑cable technicians and contingency crews.

Operational trade‑offs and economics

Owning vessels shortens timelines for repair and enables sovereignly controlled sensitive operations, but creates large fixed costs and utilization risk if demand drops. Chartering minimises capital exposure but risks delayed access, legal entanglements and limited control during contested incidents. Both approaches require complementary investments: pre‑positioned spares, trained crews, domestic shipyard maintenance, secure logistics for cable components and legal frameworks for operations in foreign waters. For Australia, the economic stake is emphasised by the scale of global financial flows traversing cables — quoted estimates place daily values in the trillions — making underwater network disruption a systemic financial risk. Japan’s subsidy is a direct state intervention to tilt the trade‑off toward assured capacity; Australia’s response mixes technical redundancy with social policy to ensure capacity can be staffed and defended.

Legal, diplomatic and attribution challenges

Damage to cables in international waters is a legally grey zone; proving culpability, pursuing offenders and mounting a timely political response are all difficult. Ownership opacity of repair and merchant vessels compounds deniability. Subsidised fleet ownership or allied pooling reduces reliance on opaque third parties, but also raises diplomatic sensitivities about dual use and perceptions of militarisation. Both countries will need clear legal rules of engagement for inspection and repair missions, allied protocols for joint response, and calibrated public framing that emphasises civilian continuity and economic stability rather than escalation.

Alliance and cooperative options

Shared fleets, reciprocal repair agreements and coordinated patrols of landing zones amplify deterrence and reduce single‑state burden. Japan’s state‑backed vessels could support allied repairs in the Indo‑Pacific; Australia’s investments in route diversity and surge crews fit naturally into a pooled regional resilience architecture. Cost‑sharing, pre‑agreed legal authorities for joint missions, and common forensic standards for attribution can shorten response times and strengthen multilateral signalling without turning civilian infrastructure into an overtly military instrument.

Human factors and societal resilience

Technical solutions fail without trained personnel and public buy‑in. Recruiting and retaining cable technicians, mariners and rapid‑response teams requires targeted training pipelines, certification regimes and career incentives. Australia’s civic renewal proposals — national service, civic education, community infrastructure projects — are presented as force‑multipliers: they supply human resources, create local ownership of projects and make mobilisation politically sustainable. Japan’s subsidy must be matched by crew training, domestic maintenance capacity and workforce policies so vessels are operationally ready when needed.

Practical near-term actions

- Build capacity while sharing cost risk: subsidise vessel acquisition with conditional allied access and shared maintenance plans.

- Expand redundancy: fund alternate routes and additional landing sites; boost onshore data‑centre capacity near secure cables.

- Institutionalise rapid response: certify and pre‑position crews; pre‑negotiate port and overflight access with partners; stock spare cable and repeaters.

- Strengthen legal frameworks: clarify rules for repair operations in international waters; harmonise attribution and evidence standards for law enforcement.

- Invest in people and civic resilience: launch targeted training pipelines for cable technicians; fund civic programmes that tie infrastructure projects to community building.

- Finance and insurance: create contingency funds and risk pools to support small suppliers and prevent cascading economic failures after an incident.

Red Sea Precedent: Campaign‑Style Disruption and Cross‑Regional Impact

Like the Baltic and suspected U.S.–Taiwan incidents cited earlier, the Red Sea event underlines the common operational problems—attribution difficulty, slow repairs and systemic financial risk—that make sovereign repair capacity and allied cooperation urgent priorities. Undersea cable outages in the Red Sea — multiple cuts that degraded connectivity across parts of Asia and the Middle East and implicated major systems such as SMW4 and IMEWE near Jeddah — provide a recent, concrete example of campaign‑style disruption: outages propagated across India, Pakistan and the Gulf, operators cited increased latency and service degradation, and monitoring groups linked the incident to broader regional hostilities. The Red Sea case highlights how non‑state or proxy campaigns, operating in congested maritime chokepoints, can weaponise commercial maritime activity and anchors to produce rapid, widespread digital effects, further complicating attribution and legal response while increasing the urgency of shared patrols, forensic standards and pre‑positioned repair assets.

Conclusion

The Red Sea precedent reframes subsea‑cable protection as a multidomain strategic task requiring industrial policy, maritime security, allied burden‑sharing and social investment in parallel. Japan’s vessel subsidies and Australia’s civic‑and‑redundancy approach are each necessary but incomplete on their own; the immediate policy goal is an interoperable ensemble of national capabilities, allied pooling and social mobilisation so that cuts are repaired fast, attribution is credible and the political will to defend open networks is durable.

Download the Full Report (pdf)