PromptLock and the New Malware Architecture: How Local LLMs Could Change Ransomware

September 3, 2025

PromptLock is a proof‑of‑concept that ties conventional ransomware tradecraft to a locally hosted large language model, showing how generative AI can be embedded into the malware lifecycle to automate and adapt post‑compromise activities. Beyond the specific sample, the real significance is architectural: malware that can query a local LLM to synthesize scripts, tailor behavior to the environment, and produce extortion content reduces the manual work attackers must perform and increases the pace at which bespoke tools and tactics can be generated.

Viewed more broadly, PromptLock highlights three strategic shifts defenders must confront. First, attack automation will move from scripted toolkits toward on‑demand code synthesis, producing dynamically generated payloads that can evade signature‑based detection and complicate forensic analysis. Second, reliance on local or proxied LLM endpoints creates a new high‑value target and a new dependency in attacker playbooks; networks that host or proxy LLMs become attractive pivot points or enablers. Third, the skill floor for complex operations will fall as generative models supply environment‑specific code and messaging, increasing the potential scale and customization of attacks.

The immediate practical risk is constrained by material prerequisites: accessible local LLM instances, permissive network segmentation, and absent prompt guardrails. The broader operational risk is that the pattern—malware prompting models to produce executable scripts—creates a repeatable blueprint attackers can refine. Defenders should therefore treat LLM hosting and access controls as core parts of enterprise risk posture, extend monitoring to detect model‑related traffic and runtime script generation, and accelerate policies that restrict or harden on‑premises model endpoints.

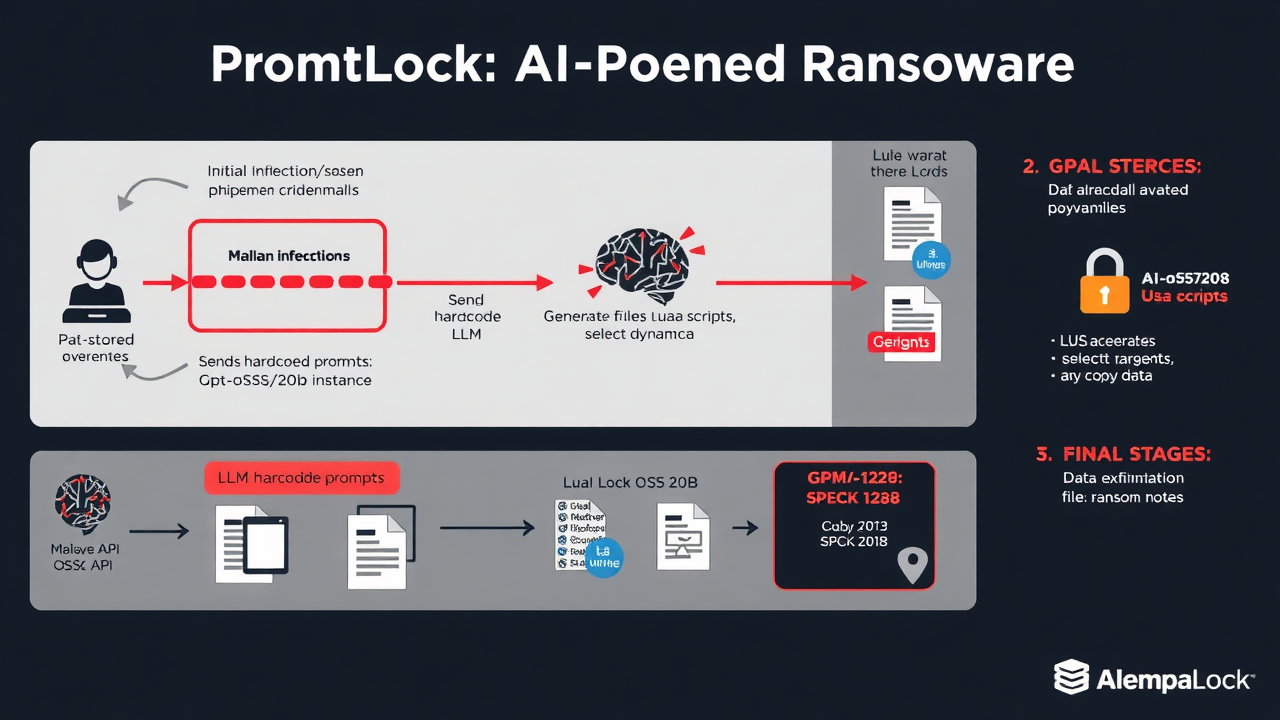

PromptLock is a proof‑of‑concept ransomware that ties conventional malware tactics to a locally hosted large language model, automating parts of the post‑compromise playbook that used to require human operators. Discovered by ESET, the sample is written in Go and is designed to call GPT‑OSS:20b through an Ollama API instance to generate Lua scripts on the fly. Those generated scripts are then executed on the infected host to perform routine attacker tasks: enumerate files and folders, inspect and select targets, copy data offsite, and encrypt files using the SPECK‑128 cipher. The code contains hard‑coded prompts that tell the model what scripts to produce; the Lua outputs are cross‑platform so the same generated script can run on Windows and Linux endpoints.

At a glance, PromptLock looks like traditional ransomware: it can find and lock user files, prepare extortion messaging, and stage exfiltration. The novel element is the delegation of script generation and some decision logic to a local LLM. Instead of a human writing dozens of bespoke scripts, the malware asks the model to produce them as needed, potentially tailoring actions to the environment it finds. ESET’s analysis shows the authors anticipated multiple outcomes—exfiltrate, encrypt, or even destroy files—but the destructive option appears not yet implemented; overall, ESET treats the sample as an experimental, not yet deployed, weapon.

That design creates several important constraints. PromptLock depends on access to a running instance of GPT‑OSS:20b reachable via Ollama. Large models at that scale normally require substantial CPU/GPU and storage resources, so most typical endpoints do not host them locally. The sample seems to probe the local network for an Ollama server or an internal proxy that will forward LLM queries, meaning it succeeds only in networks with weak segmentation or permissive outbound rules. In practical terms, the malware is unlikely to run “as is” in well‑managed environments; it is more a demonstration of concept than an immediate mass‑market threat.

Operationally the malware’s lifecycle as observed is straightforward: an initial foothold is needed (phishing, stolen credentials, or exploitation), the code attempts to locate an LLM endpoint, it sends hard‑coded prompts and receives Lua scripts, those scripts run to enumerate and package data, and then the tool can exfiltrate data and encrypt files with SPECK‑128. The presence of SPECK‑128–encrypted files and the generation of ransom messages would be the final visible stages in that chain. ESET flagged indicators such as unusual local requests to Ollama ports, runtime creation and execution of Lua scripts, rapid bulk reads and outbound transfers, and the emergence of encrypted files plus ransom notes.

Two aspects make the PromptLock story notable beyond the immediate technical novelty. First, delegating script generation to an LLM lowers the skill floor for perpetrators: attackers can automate crafting of environment‑specific tools and potentially generate more convincing social‑engineering text. Second, it shows a new attacker design pattern where dynamic code synthesis is integrated into the malware lifecycle, enabling greater adaptability and faster iteration of attack techniques. Those features matter even if the specific sample remains a PoC, because they outline a clear evolutionary path for future malware development.

ESET’s public messaging emphasises awareness and further research: the sample has not been observed in active campaigns, and key operational preconditions (local LLM availability, permissive networks, absent prompt guardrails) limit its immediate reach. The analysis also surfaces practical detection signals defenders could look for: unexpected Ollama/GPT endpoint traffic on local networks, the runtime creation of Lua files, sudden bulk file access and transfers, and the appearance of SPECK‑128 encrypted artifacts.

In plain terms: PromptLock is a prototype that replaces some human scripting with an on‑premises LLM. It demonstrates how attackers might use generative models to automate and scale post‑compromise tasks, but it also depends on nontrivial prerequisites that keep it from being an overnight epidemic. The sample’s significance lies less in present danger than in the new architecture it reveals—a model that can be prompted by malware to produce executable payloads—and in the conversations it provokes about how defenders detect, restrict and monitor access to local LLM services and dynamically generated code.

Bottom line

PromptLock is an illustrative proof that attackers could combine local LLMs with malware to automate post‑infection tasks. That combination raises future risk but also has clear practical constraints today: it needs local model access, permissive network setups, and is, for now, a concept rather than an observed active threat.

What Makes PromptLock Ransomware Unique

- First-of-its-kind: Combines traditional malware with local AI models

- Dynamic Script Generation: Uses GPT-OSS:20b via Ollama API to create Lua scripts on-demand

- Proof-of-Concept: Currently experimental, not deployed in active campaigns

Technical Workflow

- Initial Compromise → Phishing, credential theft, or exploitation

- LLM Discovery → Searches for local Ollama API endpoints

- Prompt Injection → Sends hardcoded prompts to generate malicious scripts

- Script Execution → Runs generated Lua scripts for:

- File enumeration

- Target selection

- Data copying

- Final Payload → Data exfiltration + SPECK-128 encryption + ransom notes

Current Limitations

- High Resource Requirements: Needs substantial CPU/GPU for local LLM

- Network Dependencies: Requires permissive outbound rules

- Infrastructure Prerequisites: Local Ollama server access needed

Detection Indicators

- Unusual Ollama port traffic (typically 11434)

- Runtime Lua script creation

- Bulk file access patterns

- SPECK-128 encrypted artifacts

- Suspicious LLM API queries

Future Implications

This represents a new evolutionary path for malware development, where attackers could:

- Lower skill barriers for creating environment-specific tools

- Generate more convincing social engineering content

- Adapt attack techniques dynamically