North Korea’s KONNI Cluster Weaponizes Google’s Find My Device: A New Phase in DPRK Android Targeting

November 18, 2025

North Korean operators from the KONNI activity cluster—affiliated with Kimsuky and APT37—have begun exploiting Google’s Find My Device ecosystem as part of an expanded campaign against South Korean individuals. By combining credential theft, RAT deployment, and spear-phishing via KakaoTalk, the group now leverages legitimate cloud-based security features to locate and remotely wipe Android devices. This tactic not only disrupts victims’ ability to seek help or recover accounts but also turns device-protection tools into mechanisms of isolation and cover. The campaign reflects a broader DPRK trend: shifting from conventional malware dependence to strategic abuse of trusted platforms, where identity compromise becomes the starting point for both espionage and disruption.

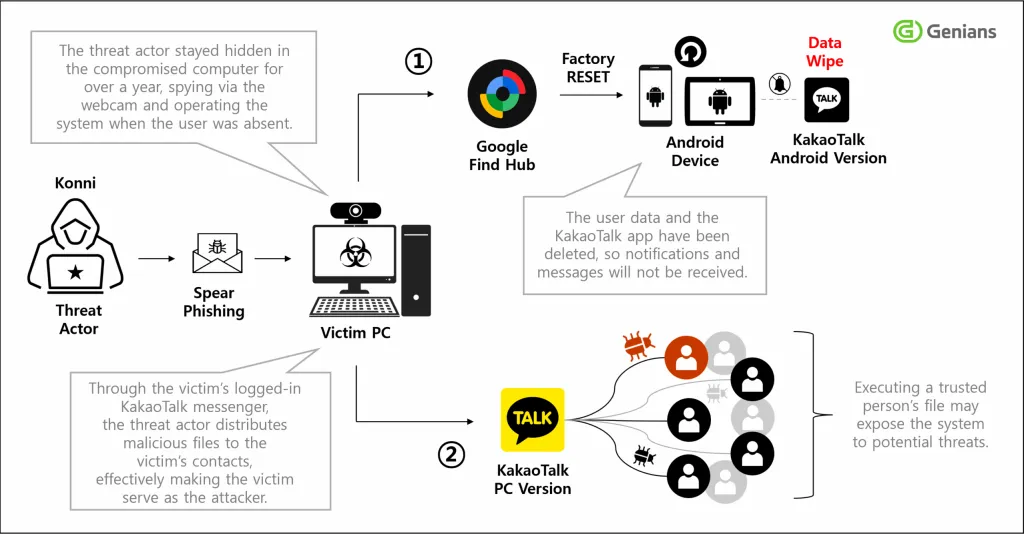

North Korean operators from the KONNI activity cluster have recently expanded their tradecraft by weaponizing Google’s Find My Device / Find Hub ecosystem, turning a security feature meant to assist users into a mechanism for remote data-wiping and device isolation. The operation, uncovered by Genians researchers, shows a deliberate convergence between spear-phishing, remote-access tooling, credential theft, and abuse of legitimate cloud-based device management services. It situates itself within the broader evolution of Kimsuky and APT37, both known for persistent targeting of South Korean civil society, defectors, researchers, and government-adjacent individuals.

The intrusion chain begins with highly contextualized social engineering. KakaoTalk—the dominant communication platform in South Korea—serves as the primary delivery channel. The attackers spoof institutional identities such as the National Tax Service, law-enforcement units, or administrative bodies addressing fabricated issues requiring the victim’s attention. Attached files present themselves as benign documents or patches; in reality, opening them triggers an AutoIT loader responsible for orchestrating second-stage execution.

The malware ecosystem behind the initial loader is familiar yet adapted. RemcosRAT, QuasarRAT, and the group’s custom RftRAT appear in varying combinations, giving operators the ability to log keystrokes, exfiltrate browser credentials, collect system metadata, and deploy additional scripts at will. Once the machine is fully compromised, the attackers pivot toward cloud accounts, harvesting Google logins that allow them to enter the victim's device-management dashboard.

From this position, the group leverages Google’s Find Hub functionalities—specifically the location-tracking and remote-reset features—to identify the victim’s registered Android devices and wipe them. The intent is not mere sabotage; wiping the phone removes communication history, authentication tokens, and stored data that could help the victim recover accounts, alert contacts, or report the attack quickly. In several documented cases, the reset command is executed repeatedly to eliminate any possibility of data recovery and to sever the victim from digital support structures.

One example illustrates this modus operandi. On September 5, a counselor working with North Korean defectors unknowingly had their KakaoTalk account hijacked, allowing KONNI operators to send a malicious file to individuals within their network. After compromising at least one target, the attackers moved to the Google account associated with the victim’s Android device and initiated multiple remote wipes. In parallel, the compromised KakaoTalk identity was used to continue spreading the infection, turning each victim’s contact network into a cascade of new targeting opportunities.

The abuse of Google Find Hub underscores a broader pattern: North Korean APT units increasingly weaponize legitimate cloud tools and account-recovery functions. Instead of relying exclusively on crafted exploits or custom implants, they exploit trust relationships and the automation of user-protection features. This strategy not only lowers detection by endpoint security tools but also complicates attribution at early stages, since actions appear to originate from normal account activity using valid credentials.

Across the Android ecosystem, the implications are significant. Remote wipe capabilities—normally reserved for anti-theft scenarios—can become instruments of coercion and operational cover: erasing incriminating traces, preventing victims from seeking assistance, or collapsing a defender’s early-response window. For South Korea, where Google’s ecosystem and KakaoTalk account for major elements of digital life, these attacks represent not just technical incursions but social and psychological pressure points leveraged by North Korean intelligence services.

The campaign also reflects a consistent strategic theme in DPRK cyber operations: the integration of espionage, disruption, and social infiltration. KONNI’s practices mirror a model in which credential theft leads to identity hijacking, identity hijacking leads to lateral social propagation, and cloud-service manipulation provides both control and deniability. While the total scope remains unclear, experts warn that the volume of abnormal Google account logins and remote-reset events may be higher than currently reported, given the difficulty victims face in recognizing the compromise before their devices are wiped.

In this environment, mitigation becomes a matter of hygiene rather than advanced technical defense: strict enforcement of two-factor authentication across all Google accounts; skepticism toward unsolicited KakaoTalk attachments, even from trusted contacts; periodic auditing of devices linked to cloud accounts; and immediate investigation of abnormal login alerts. Yet these steps only partially address the structural problem revealed by the KONNI campaign—legitimate cloud features can be reprogrammed into tools of coercion once credentials are stolen.

As long as geopolitical tensions persist and South Korean civil society remains a strategic intelligence target, the DPRK’s cyber services are likely to intensify their use of identity compromise and cloud-service manipulation rather than abandon it. The KONNI operation serves as another reminder that today’s APT threat is less about zero-day exploits than about disciplined, iterative abuse of the tools people rely on every day.