Hybrid Cyber Frontiers: Unraveling Russia, China and North Korea’s State–Non-State Playbooks

September 1, 2025

In today’s cyber arena, authoritarian regimes fuse state objectives with non-state actors to turn digital crime into strategic leverage. Russia’s criminal safe-havens, China’s vast contractor ecosystem and North Korea’s crypto-driven espionage each blend official directives with external talent to gain agility and plausible deniability. These hybrid moduses operandi outpace traditional defenses, forcing democracies to rethink attribution-dependent tools and build a more flexible, coordinated response framework. Understanding how Moscow, Beijing and Pyongyang exploit non-state capabilities is the first step toward countering their fragmented yet formidable assaults.

Blurring the Line Between State and Non-State

Authoritarian regimes are erasing the boundaries between state and non-state activity in cyberspace. By leveraging criminal groups, hacktivists, and loosely aligned contractors, they extend their reach while muddying attribution, complicating international responses. The old question of “who did it” matters less when operations are entangled; what matters now are trusted partnerships, intelligence sharing, and tools that can operate even when attribution runs cold.

Beyond State Adversaries

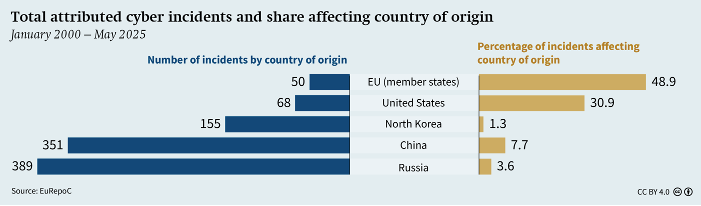

For years, Western assessments have centered on state adversaries. EuRepoC tracks more than 600 state-backed groups, but four countries—China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea—account for over 70 percent of state-linked threats to Europe and its partners since 2000. Their activity spans intellectual property theft, espionage, and attacks on critical services, justifying their prominence. Yet state operations represent only 29 percent of recorded incidents. The rest are driven by criminals and hacktivists, pursuing the same targets for extortion or disruption. This imbalance reveals how authoritarian states cultivate hybrid ecosystems where non-state actors play decisive roles.

Distinct National Models of Hybrid Power

Russia, China, and North Korea embody different models of this fusion. Moscow’s safe-haven strategy offers protection and tacit license to criminal groups, unleashing ransomware syndicates and disposable proxies that bleed adversaries while shielding the state from attribution. Beijing’s industrialized espionage machine channels zero-day hunters, exploit brokers, and commercial contractors into military and intelligence hierarchies, producing precision strikes with plausible deniability. Pyongyang, meanwhile, relies on global reach—embedding hackers in IT firms abroad, planting crypto “laptop farms,” and laundering ransomware proceeds into its nuclear program. Three paths, one logic: expand state power through ambiguity, scale, and resilience.

The Limits of Attribution-Based Responses

Traditional responses anchored in attribution are faltering. Sanctions, indictments, and travel bans remain important, but adversaries adapt faster than attribution cycles can keep pace. As Germany’s cyber ambassador Maria Adebahr argued in 2025, waiting for perfect attribution only cedes time and initiative to hostile actors. Democracies need flexible tools that remain effective even when the trail is murky.

Building a Layered Defense

Meeting hybrid threats requires a dynamic, multifaceted response. Diplomatically, authoritarian-linked operators must be cut off from platforms and cloud services. Criminal infrastructure—malware marketplaces, bulletproof hosting, orphan-routing blocks—must be dismantled through coordinated takedowns. Intelligence fusion across the EU, Five Eyes, and Asia-Pacific partners is essential to shrink safe havens. Legal guardrails should enforce due diligence by service providers, while technical countermeasures—automated blocking, threat-feed integration, covert disruption of command nodes—must be deployed at the speed of attack. The challenge for Europe and its allies is to abandon outdated distinctions between state and non-state threats and build strategies calibrated to the hybridity of modern cyber power.

Russia, China, and North Korea each embody distinct doctrines that illuminate the diverse ways authoritarian regimes are weaponizing cyberspace. Moscow thrives on permissive chaos, shielding criminal groups to generate disruptive power at scale. Beijing has industrialized espionage, fusing state-directed programs with a vast commercial hacking ecosystem. Pyongyang, under the weight of sanctions, has forged a model where cyber operations directly fuel its strategic survival, from missile funding to global illicit finance. Taken together, these doctrines illustrate not just varied tactics, but systemic approaches that exploit ambiguity, expand reach, and challenge the resilience of democratic responses.

Russia’s Cybercrime Social Contract

Russia has quietly transformed its cybercriminal underworld into a strategic safe haven, and nowhere is that more obvious than in Germany’s notorious most-wanted list. Nearly half the names on the list are Russian cyber operators—individuals accused of everything from high-stakes fraud to collusion in state-level hacking—and yet despite Germany’s strong track record of 70 percent arrest rates since 1999, those linked to Russia almost never face prosecution. That’s not happenstance. It’s the result of an unspoken “social contract” between the Kremlin’s security services and local criminal syndicates: as long as they steer clear of Russian targets and occasionally do the state’s bidding, hackers are left free to prey on foreign networks without fear of extradition or jail time.

This laissez-faire arrangement has turned Russia into a magnet for malicious cyber actors. Data from the European Repositories of Cyber Incidents (EuRepoC) shows that only 3.6 percent of attacks traced back to Russia hit domestic systems. By comparison, China’s home-grown operations strike its own networks at twice that rate, and in the United States and EU it’s eight and fourteen times higher, respectively. Even the malware itself betrays the carve-out: Ryuk ransomware, for example, checks a computer’s language settings and self-destructs if it senses Russian locales.

Efforts to crack down on these criminal havens have been sporadic, but rarely decisive. In 2009, FBI and Secret Service agents traveled to Moscow convinced they’d watch Russian authorities arrest Roman Seleznev—wanted for stealing millions of credit card records—but he slipped away thanks to FSB tip-offs. Only after holidaying in the Maldives five years later did Seleznev finally face justice in a U.S. courtroom, where he received a 27-year sentence before being swapped back to Russia in the August 2024 prisoner exchange.

Learning from that scant victory, international law enforcement has shifted tactics. Operation Endgame set out not just to snag criminals but to dismantle their digital scaffolding. In its second phase, German authorities joined forces with partners to seize 300 servers and shut down 650 domains tied to Russia-based groups. Arrest warrants for twenty suspects made headlines, but insiders note that disruption of infrastructure—more than indictments—has become the real metric of success.

Far from eroding the safe-haven model, these moves have reinforced state-criminal symbiosis. As the full-scale invasion of Ukraine strained the People’s Liberation Army’s cyber units, Moscow leaned ever harder on criminal crews as a cost-effective boost. When the Trickbot group publicly aligned with the Kremlin in February 2022, leaked chats showed it had already been liaising with the FSB since spring 2021 on targeting regime critics—a partnership that predates the war itself.

Long before the tanks rolled in, FSB handlers were recruiting known hackers to stretch state capabilities. In 2017, U.S. indictments named Aleksey Belan and two FSB officers who approached him in early 2014 to hack Yahoo and harvest half a billion account credentials. Belan, notorious enough to be on the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list and briefly arrested in Greece, found sanctuary in Russia, where even his legal troubles became cover for deeper clandestine missions.

At the heart of this tangled web sits the FSB’s Centre 18—unit 64829—ostensibly Russia’s cybercrime division. It collects intelligence on criminal networks to recruit talent, oversees its own espionage teams like Star Blizzard, and coordinates operations with regional clusters such as Gamaredon in occupied Crimea. These groups target everything from NATO governments to Ukrainian power grids, blurring the line between state action and criminal enterprise.

By offering hackers impunity in return for occasional state-assigned tasks, Russia has built a blueprint for cyber “active defense” that thrives on ambiguity. Criminal syndicates operate openly against foreign targets, while their state sponsors reap the strategic benefits—cost imposition, political pressure, plausible deniability—without ever firing a shot. It’s a model that other authoritarian regimes watch closely—and one that democracies are still scrambling to counter.

Russia’s intelligence agencies don’t just tolerate criminal hackers—they have learned to weaponize their tools and networks. In June 2017, for example, GRU’s Unit 74455 ripped the encryption engine from a familiar ransomware kit and rewrote it for unstoppable, irreversible destruction—unleashing the NotPetya wave that trashed corporate and government systems worldwide.

Behind the scenes, another GRU outfit—Unit 26165, nicknamed “Void Blizzard”—buys stolen credentials in underground markets and uses them to slip into the most sensitive NATO and EU targets: foreign ministries, defense firms, tech contractors, political parties and news outlets. Their tradecraft mirrors that of top-tier crime groups, making their operations nearly indistinguishable from pure criminal activity.

Even criminal toolmakers play along. The DanaBot network, originally built to steal data and deliver malware, now ships two versions: one for ransomware affiliates, and a stealthier “espionage” edition sold—likely to state actors—to vacuum up military, diplomatic and NGO communications. To keep their ill-gotten gains safe, all exfiltrated data is quietly funneled into Russian-based servers.

Moscow’s appetite for non-state assets extends beyond code. In late 2024, Western security services uncovered a GRU plot that recruited “disposable” proxies across Europe to plant explosive packages on cargo planes bound for North America. By outsourcing these final, most visible steps, Russia shields its own operatives and blunts diplomatic fallout if a scheme collapses.

This deliberate mix of state and criminal operatives creates a rotating cast of hackers and saboteurs. If one node is exposed or disrupted—by an arrest warrant or a server seizure—the rest simply adapt. Tasks are compartmentalized so tightly that cracking one cell tells investigators almost nothing about the next.

At the center of this hybrid model sits the FSB’s Centre 18 (military unit 64829), which on paper fights cybercrime but in practice recruits top offenders, steers clandestine espionage squads like Star Blizzard, and oversees proxy clusters such as the Gamaredon network in occupied Crimea. By blending invisible chains of command and shared criminal tooling, Russia has turned its underworld into an expendable yet endlessly renewable cyberweapon—one democracies are only beginning to grasp how to counter.

China: Command. Control. Deniability.

China’s cyber strategy is built on a three-pronged formula: command, control and deniability. Instead of simply co-opting criminal crews, Beijing has deliberately nurtured a commercial hacking ecosystem to feed its state objectives. At the top of the pyramid sits the military. After major reorganizations in 2015 and again in April 2024, most offensive cyber assets were folded into the PLA’s Strategic Support Force and then elevated into a dedicated Cyberspace Force under the direct supervision of the Central Military Commission. This move ensures that all high-risk operations—from paralysis of foreign power grids to disruption of critical communications—are ordered centrally and executed with military precision.

Beneath the PLA’s iron fist, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) has become the nerve center for espionage. The MSS’s 13th Bureau runs China’s National Vulnerability Database and sponsors a series of hack-and-defend competitions to harvest every newly discovered flaw. Winning entries and exploit toolkits flow straight into MSS offensive programs, but the heavy lifting is outsourced to scores of private contractors. More than a hundred firms now compete to develop zero-day exploits, craft bespoke malware and even mount initial breaches—yet none carry a state emblem on their sleeve.

Those contractors, managed by so-called “digital quartermasters,” blur the line between mercenary hacker and spymaster. They report vulnerabilities, build attack frameworks and often run operations themselves, giving Beijing plausible deniability. When a data center goes dark, investigators find digital breadcrumbs pointing to independent crime gangs or freelance “hack-for-hire” outfits, never the Chinese state. And by meshing together hijacked routers and servers in third countries—so-called orphan routing blocks—those contractors create shadow infrastructure that keeps true origin undetectable.

This sprawling network of private players also carries outsized risk. Contractors sometimes cross the invisible line into pure financial crime, dropping ransomware on targets when remediation teams close in. In April 2020, for instance, researchers tied to Sichuan Silence exploited a new firewall vulnerability to breach more than 81,000 devices—and then seeded ransomware as a cover-up tactic. Had those attacks hit a U.S. energy company’s offshore rig, Treasury officials warned, lives could have been endangered. That incident laid bare the peril of outsourcing destructive actions to loosely governed entities.

China’s model isn’t static—it evolves in response to strategic needs. When the PLA’s cyber units were stretched thin by other priorities, MSS contractors filled the gap, stepping up espionage and sabotage roles at a fraction of the cost. This on-demand, compartmentalized structure means that if one contractor’s infrastructure is taken down or one team is exposed, dozens of others can carry on unabated. Each node’s autonomy makes the entire ecosystem resilient against law-enforcement crackdowns and attribution efforts.

Disentangling state actors from criminal proxies has become a forensic nightmare. Clusters like I-Soon, APT27 and Silk Typhoon collaborate seamlessly, swapping code, data feeds and access points. Sometimes they monetize their breaches with extortion; other times they deliver stolen communications directly to MSS analysts. The result is a cyber-espionage machine that operates with the agility of a start-up and the backing of a superpower.

Ultimately, China’s command-control-deny doctrine forces defenders into a modern Catch-22. Tightening laws against private hacking firms risks driving talented exploit developers into the arms of the state. Publicly exposing vulnerabilities aids domestic security but also teaches Beijing how to patch its own systems faster. For nations grappling with this hybrid threat, the challenge is twofold: build attribution tools that can pierce the veil of orphan routing and hold the party in Beijing accountable, while simultaneously disrupting the contractor networks before they can churn out the next generation of destructive exploits.

North Korea: Breaking Isolation & Crypto-Fueled Cyber Expansion

North Korea’s cyber program is a paradox: it reinforces the regime’s doctrine of self-reliance even as it reaches out beyond the DMZ to tap global expertise. Pyongyang has quietly enlisted foreign blockchain engineers and cryptocurrency innovators to mask financial flows, turning legitimate platforms into vehicles for sanctions evasion. By co-opting tools from the open-source community and laundering proceeds through international exchanges, the DPRK has forged a lifeline for its nuclear and missile programs.

In 2019, that gambit played out in plain sight when Pyongyang hosted a conference for Western crypto developers. Despite FBI warnings, an Ethereum engineer flew in and wound up under indictment for violating U.S. sanctions—ultimately serving over five years behind bars. A British entrepreneur who attended sought political asylum in Russia rather than face similar charges. The episode underscored how North Korea weaponizes engagement, ensnaring unwitting experts to learn their tradecraft.

Between 2017 and 2023, DPRK-linked hackers stole an estimated $3 billion from cryptocurrency exchanges and DeFi projects. These “revenue operations” are run by units inside the Reconnaissance General Bureau—the military intelligence arm responsible for both espionage and theft. Groups like Andariel funneled ransoms from U.S. and South Korean healthcare targets back into the bureau’s offensive cyber infrastructure, which in turn has been used to breach defense contractors, aerospace firms and uranium-processing sites.

To escape Pyongyang’s digital gaze, North Korean APTs have built a web of overseas footholds. Agents pose as remote IT contractors in China and Southeast Asia, piggybacking on local firms to hide their origins. Security firms have pinpointed clusters of “laptop farms” in at least eight U.S. states and pockets of the U.K., Poland and Romania—each a staging ground for intrusions that appear indistinguishable from local cybercrime.

In late 2024, some operatives even escalated to full-blown extortion: upon detection they threatened to publish stolen data unless ransoms were paid. Mandiant analysts called this shift an “exit scheme,” designed to squeeze maximum value from each compromise. DTEX Intelligence reported rare instances where attackers dangled network access to other DPRK APTs, turning victims into unwilling gateways for deeper exploitation.

Recognizing the value of lessons learned abroad, the RGB launched Research Centre 227 in March 2025. Tasked with “developing offensive hacking technologies and programmes,” it will feed real-time insights from overseas deployments back into Pyongyang’s core cyber apparatus. By institutionalizing that feedback loop, North Korea aims to refine its capabilities faster than any sanctions-ridden adversary can disrupt them.

Across these efforts, the DPRK has blurred the line between state and non-state, legal and illicit. From subverting international crypto norms to running shadow networks in foreign lands, its cyber operators have turned isolation into opportunity—and created a challenge that outpaces traditional law enforcement and attribution. Democracies must now find new ways to trace that tangled web of proxies, disrupt the money flows and close the loopholes that North Korea exploits to break out of its isolation.