Europe Putin the blame on Russia after GPS jamming disrupts president’s plane

September 2, 2025

When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s aircraft experienced a sudden loss of GPS navigation while approaching Plovdiv, Bulgaria, the event was quickly framed by authorities as suspected jamming and placed against a wider pattern of GNSS interference across Europe’s eastern and littoral corridors. Pilots reverted to alternative aids and manual procedures and landed safely, but the incident highlighted a fragile dependence on satellite positioning and timing, exposed gaps in rapid forensic attribution, and generated immediate political alarm. Public briefings and agency statements treated the episode not as an isolated technical fault but as part of an intensifying electromagnetic contest, prompting discussion of layered technical mitigations — from expanded LEO satellite capacity and distributed RF sensing to harmonized reporting and tighter export controls on jamming devices — while underscoring the strategic stakes for civil, commercial and military systems.

The incident and immediate operational facts

As Ursula von der Leyen’s aircraft approached Plovdiv, Bulgaria, crew instruments began to show unreliable or absent satellite navigation fixes. Pilots reported a GPS problem during final approach, circled the airport while switching from automated guidance to alternative electronic aids and paper charts, and completed a safe landing after about 23 minutes of manoeuvring. Bulgarian authorities publicly described the event as a GPS outage in the airport area and said they suspected external interference; the European Commission confirmed GPS jamming occurred and reported that initial information from Bulgarian authorities pointed to deliberate interference. Moscow’s official response was a denial.

Flight recordings and public accounts report a sudden, localized loss of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) signals across the airport approach corridor rather than a broad satellite outage affecting large swathes of sky. Some nearby aircraft and online position trackers showed normal operations, leading analysts to consider whether the effect was narrowly targeted at the presidential flight or part of a concentrated jamming field. Pilots performed established degraded‑navigation procedures, using radio aids and manual navigation — techniques that are effective but increase crew workload and compress safety margins during critical flight phases.

Technical signature, detection and forensic needs

The behaviour described — abrupt loss of fixes, inconsistent position/time reads and a geographically constrained signal blackout — is characteristic of terrestrial jamming or spoofing. Jamming involves transmitting high‑power radio signals on GNSS frequencies to overwhelm weak satellite signals; spoofing involves transmitting counterfeit GNSS signals that mislead receivers about location or time. Distinguishing between the two requires multi‑site RF captures, time‑stamped receiver logs, Doppler and power‑profile analysis, and cross‑correlation with independent monitoring stations.

Effective forensic attribution therefore depends on rapid, coordinated evidence capture: preserved receiver logs from affected aircraft and ground systems; spectrum recordings from distributed sensors; timestamp synchronisation across observatories; and physical records of potential terrestrial emitters. Without standardised capture formats and pre‑arranged cross‑border data‑sharing protocols, assembling a defensible chain of technical evidence is slow and politically costly. That technical delay is precisely what makes spectrum interference a useful gray‑zone tool: it creates operational disruption while stretching attribution timelines.

Geographic pattern and historical context

The Plovdiv event sits within a documented increase of GNSS anomalies across Northern, Baltic and Eastern Europe since 2022. Reports from civil operators, military crews and maritime users show clusters of jamming and spoofing events near littoral and transit corridors, with notable concentrations on the eastern flank. National authorities and alliance spokespeople describe a pattern of repeated, sometimes geographically concentrated episodes that affect aircraft approaches, vessel navigation and civilian positioning services in port approaches and coastal waters. Observers draw a line between those tactical disruptions and a broader portfolio of hybrid actions reported in the region, ranging from undersea cable damage and cyberattacks to sabotage and covert operations.

Political readings and allied posture

EU and NATO officials publicly framed the Plovdiv disruption as part of a rising campaign of hybrid threats. NATO leaders described spectrum interference as one among several destabilising tactics now in play, while EU spokespeople characterised the eastern flank as especially exposed. High‑level rhetoric invoked the need for deterrence and collective response; statements emphasised that jamming and spoofing are not mere nuisances but instruments that can erode operational certainty across civil and military domains. At the same time, political leaders emphasised the operational reality that commercial air travel remains safe because crews and airframes retain non‑GNSS backstops — yet they warned that persistent interference raises strategic risks and operational costs.

The political dynamics are complicated by attribution politics. Technical indicators can point strongly to terrestrial jamming fields, but tying those fields to state direction or proxy actors requires corroborating intelligence and diplomatic corroboration. Public accusations, denials and the pace at which technical teams can produce convincing evidence all shape the diplomatic response cycle. The incident therefore functions as both a technical problem and a political signal — measured reactions, public demarches and coordinated evidence‑sharing become part of the response toolkit.

Policy signals reported in public briefings

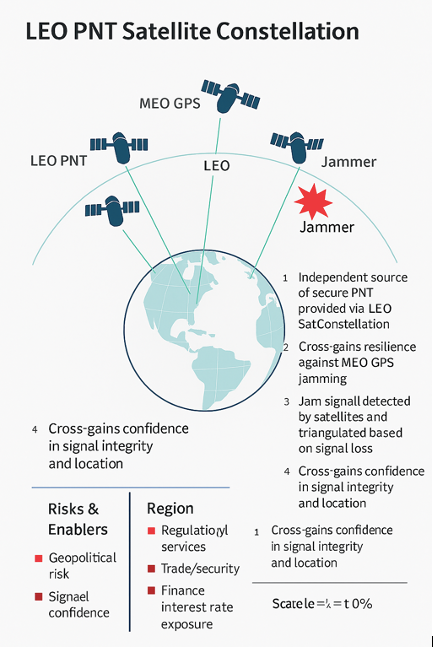

Public briefings and agency reports following the Plovdiv event emphasised a set of policy directions and technical measures rather than immediate operational decrees. These publicly discussed measures include expanding satellite capacity in low Earth orbit to provide alternative PNT layers [Positionig-Navigation-Timing] and improved interference detection; improving interference detection through distributed RF sensing and faster correlations; harmonizing incident reporting (common NOTAM/Q codes and standard radio calls for GNSS interference); tightening export and licensing controls on jamming equipment; and preserving or maintaining minimum networks of conventional radio navigation aids as GNSS backups. EASA’s mitigation framework — cited in briefings — lists harmonised RFI reporting standards, export controls on jammers, mandated backups, and strengthened civil‑military information sharing as key lines of effort. NATO officials signalled stepped‑up coordination on countermeasures and intelligence sharing.

These proposals were presented publicly as necessary but recognisably multiyear and programmatic: deploying additional LEO payloads, expanding sensor grids, and tightening export controls all require financing, procurement and international cooperation. Officials emphasised that some measures — such as simple harmonisation of reporting formats or tightening export licences for jamming hardware — are faster to implement, while satellite augmentation and comprehensive monitoring architectures are medium‑ to long‑term projects.

Traditional GPS relies on medium Earth orbit (MEO) satellites about 20,000 km up. They provide wide coverage but limited redundancy. By adding LEO satellites at a few hundred to 1,200 km, you introduce more sources of navigation signals. This means that even if GPS signals are jammed or spoofed, receivers can cross-check with LEO signals, making it harder for adversaries to completely blind or mislead users.2. Stronger signal power at ground level

LEO satellites orbit much closer to Earth, so their signals arrive much stronger than those from MEO GPS satellites. This makes them more resistant to jamming, because a jammer would have to output far more power to overpower a nearby LEO signal compared to the weaker GPS signal.3. Higher update rates and precision

Because LEO satellites move quickly across the sky, they deliver rapid changes in geometry, allowing receivers to calculate positions with higher refresh rates and improved accuracy. This agility also makes spoofing harder, since an adversary would need to replicate fast-changing signal patterns in real time.4. Multi-layered architecture for resilience

Adding LEO to the existing MEO (GPS, Galileo, BeiDou, GLONASS) and GEO (communications) layers creates a multi-orbit architecture. If one layer is degraded, others can take over. This strengthens resilience not just against interference, but also against satellite failures or cyberattacks.5. Improved interference detection

With more satellites broadcasting at different frequencies and orbits, monitoring stations and even end-user devices can compare signals across constellations. Anomalies such as unexpected delays, signal strength mismatches, or false positioning can be flagged faster, allowing quicker detection of jamming or spoofing. For example, if a GPS signal says you’re at Point A, but a LEO signal disagrees, the system can infer interference is in play.6. Global situational awareness

LEO constellations, especially if large (dozens to hundreds of satellites), can act as sensors themselves, detecting interference patterns from orbit. They can map where jamming is occurring on Earth’s surface and share that intelligence in near real time, improving defense, aviation, and critical infrastructure security.

Operational implications for aviation, maritime and defence users

Aviation authorities underlined that aircraft are equipped with multiple navigation systems and that crew training covers GNSS loss scenarios. Nonetheless, sudden GNSS disruption during approach or in high‑traffic airspace magnifies workload and reduces margins for error, particularly where legacy radio aids have been decommissioned or are degraded. Maritime navigation, logistics operations, and critical infrastructure that rely on precise timing (financial systems, telecom networks, power grids) similarly face intermittent but material risk from jamming and spoofing. For military planners the worry is both immediate (loss of precision guidance or timing for platforms and munitions) and systemic (the need to operate reliably in a contested EM environment).

Military and civilian operators have privately and publicly referenced the need for distributed RF monitoring, hardened and authenticated PNT stacks, and more robust forensic standards to support rapid geolocation and evidence building. Public statements indicated appetite for both tactical mitigations (local monitoring, fast‑build detection) and strategic investments (LEO augmentation, authenticated signal overlays), but officials repeatedly noted the resource and coordination demands of executing such programs at scale.

Strategic interpretation: an indicator of a wider contest

Read together, the incident’s technical specifics, its placement within a regionally clustered set of GNSS anomalies, and the tenor of allied political responses point to an intensifying electromagnetic component of a larger geopolitical contest. Jamming and spoofing are attractive tools for actors seeking asymmetrical influence: they are relatively low cost, can be tailored to particular corridors or targets, and create operational friction without triggering immediate kinetic escalation. When high‑profile diplomatic flights are affected, the political salience rises sharply and forces public signaling, investigative posturing and defensive spending.

This pattern matters because it shifts several policy and operational baselines. First, civil infrastructures that assumed ubiquitous GNSS availability must now budget for alternative PNT and forensic detection as ordinary resilience costs. Second, alliances must normalise cross‑border technical cooperation — common reporting standards, interoperable forensic formats and pre‑arranged sensor networks — to shorten attribution timelines. Third, the threshold for what constitutes an escalatory act in the electromagnetic domain is politically negotiated; repeated, targeted interference pressures such thresholds and incentivises both defensive hardening and potentially retaliatory doctrines.

Concluding narrative framing

The Plovdiv GPS disruption is operationally contained and resolved — the aircraft landed safely and immediate danger to passengers was avoided — but it is emblematic of a broader shift: the electromagnetic spectrum has become a theatre of low‑visibility coercion that blurs conventional lines between civilian harm and strategic signalling. Public briefings and agency plans that followed the event did not propose quick fixes so much as chart a program of resilience and detection: more LEO satellites for redundancy and detection, harmonised incident reporting, expanded RF sensor grids, tighter export controls on jamming devices, and stronger civil‑military data sharing. Those proposals acknowledge a hard truth exposed by the incident: navigation and timing security are no longer purely technical matters but core elements of geopolitical and alliance resilience.